import pandas as pd

import numpy as np9 Strings and Regular Expressions

9.1 Introduction

This chapter goes into more detail on dealing with string objects, using methods and regular expressions.

Many of the functions in this chapter are from a library called re. This is built into base python, so you do not need to install it!

9.2 String Methods

We have already seen many examples so far of objects that have the string data type. These might be referred to as str or character or object, depending on the library we are using to check type.

String objects can be combined with the + operator:

string_1 = "Moses supposes his toeses are roses,"

string_2 = "Moses supposes erroneously."

string_1 + ", but " + string_2'Moses supposes his toeses are roses,, but Moses supposes erroneously.'However, they cannot be subtracted, divided, or multiplied!

string_1 - "Moses"TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for -: 'str' and 'str'Much as we can subset lists and similar objects, we can also subset strings according to their characters:

string_1[0:5]

string_1[5:]

string_2[-12:-1]'erroneously'A list of string objects is not the same as a standalone string object! The length of a list is the number of elements it has. The length of a string is the number of characters it has.

9.2.1 Cleaning up a string

What other changes might we commonly want to make to string objects? Many of the tasks we might need to do are available in python as string methods. Recall that a method is a special function that can work only on a certain object type or structure.

For example, I might want to turn my whole string into lowercase letters, perhaps for simplicity.

string_1.lower()'moses supposes his toeses are roses,'I also might want to get rid of any extra white space that is unnecessary:

string_3 = " doot de doo de doo "

string_3.strip()'doot de doo de doo'9.2.2 Searching and replacing

Perhaps we want to make changes to the contents of a string. First, we might check to see if the word we want to change is truly present in the string:

string_4 = "My name is Bond, James Bond."

string_4.find("Bond")11Notice that this gives back the character index where the desired word starts.

If the pattern is not found, we get back a value of -1.

string_4.find("007")-1Next, we can replace the word with a different string:

string_4.replace("Bond", "Earl Jones")'My name is Earl Jones, James Earl Jones.'As with any object, nothing changes permanently until we reassign the object. The .replace() method did not alter the object string_4:

string_4'My name is Bond, James Bond.'Sometimes, when we want to build up a particularly complex string, or repeat a string alteration with different values, it is more convenient to put a “placeholder” in the string using curly brackets {} and fill the space in later.

string_4 = "My name is {}, James {}."

string_4.format("Bond", "Bond")

string_4.format("Franco", "Franco")'My name is Franco, James Franco.'The {} placeholder combined with the .format() method also allows for named placeholders, which is handy when you want to repeat a value:

string_4 = "My name is {lastname}, {firstname} {lastname}."

string_4.format(firstname = "James", lastname = "Baldwin")'My name is Baldwin, James Baldwin.'9.2.3 Splitting and joining

Sometimes, it may be convenient to convert our strings into lists of strings, or back into one single string object.

To turn a long string into a list, we split the string:

fish_string = "One fish, two fish, red fish, blue fish."

fish_list = fish_string.split(", ")

fish_list['One fish', 'two fish', 'red fish', 'blue fish.']Notice that our argument to the .split() was the pattern we wanted to split on - in this case, every time there was a comma and a space. The characters used for splitting are removed, and each remaining section becomes an object in the list.

Now that we have a list, if we want to use string methods, we can’t apply them directly to the list object:

fish_list.replace("fish", "moose")AttributeError: 'list' object has no attribute 'replace'Instead, we’ll need to iterate over the string objects in the list.

new_list = list(map(lambda x: x.replace("fish", "moose"), fish_list))

new_list['One moose', 'two moose', 'red moose', 'blue moose.']Now, if we want to recombine this list into one string, we will join all its elements together. The .join() method is a bit of a peculiar construct: we call the method on a string that we want to put between each list element when we bring them together.

" and ".join(new_list)

", ".join(new_list)'One moose, two moose, red moose, blue moose.'9.3 Regular Expressions

In the .replace() method above, we supplied the exact pattern that we wanted to replace in the string.

But what if we wanted to find or replace all approximate matches? For example, if we have the string

moses_string = "Moses supposes his toeses are roses, but Moses supposes erroneously. Moses he knowses his toeses aren't roses, as Moses supposes his toeses to be."we might be interested in finding all the rhyming words in this string, i.e., all words ending in “-oses” or “-oeses”.

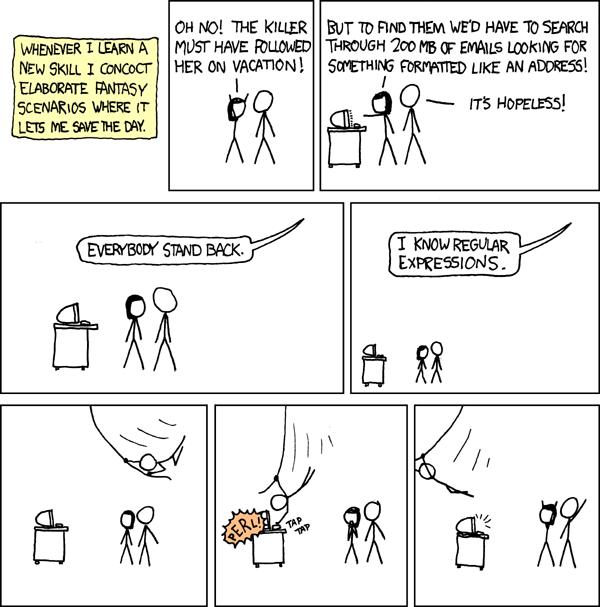

To perform this kind of fuzzy matching, we need to use regular expressions.

A regular expression is a special type of string, that can be interpreted by particular functions as a series of commands for fuzzy matching.

For example, instead of using the .findall() string method, we’ll use the very similar function re.findall() to search a string using regular expressions:

import re

re.findall(r"[Mr]oses", moses_string)['Moses', 'roses', 'Moses', 'Moses', 'roses', 'Moses']In the above code, the r in front of the regular expression "[Mr]oses" let the function know a regular expression was being provided. This isn’t always needed, but it’s a good habit to get into, to make it clear when you supplying an ordinary string (a.k.a. string literal) or a regex.

The [Mr] part of the regex told the re.findall() function to match any “M” or any “r” - so we were able to find instances of both “Moses” and “roses”!

Regular expressions can be both very powerful and very frustrating. With the right expression, you can match any complicated string bit you might want to search for in data! But putting the expressions together requires learning the special characters that lead to fuzzy matching, such as knowing that something in brackets, like [Mr] means “match either of these characters”.

9.3.1 Shortcuts

In our Moses example, we wanted to match all rhyming words. Rather than go through the whole string to figure out possible letters that come before “-oses”, we can instead use the \w regular expression shortcut to say “match any character that might be found in a word” - i.e., not punctuation or whitespace.

re.findall(r"\woses", moses_string)['Moses',

'poses',

'roses',

'Moses',

'poses',

'Moses',

'roses',

'Moses',

'poses']Other handy shortcuts include:

\b: “boundary” between word and non-word, such as punctuation or whitespace\s: “space” matches a single whitespace character\d: “digit” matches any single number 0-9^: matches the start of a string$: matches the end of a string.: matches any character at all, except a new line (\n)

9.3.2 Repetition

We still haven’t quite completed our goal of finding the rhyming words, because we were only able to match the string “poses” instead of the full word “supposes”.

An important set of special symbols in regular expressions are those that control how many of a particular character to look for. For example,

names = "Key, Kely, Kelly, Kellly, Kelllly"

re.findall(r"Kel+y", names)['Kely', 'Kelly', 'Kellly', 'Kelllly']In this regex, the + character means “match the previous thing at least one time”. Since the thing before the + is the letter l, we match any string that starts with “Ke”, then has one or more l’s, then has a y.

Other regex symbols for repetition are:

*: Match 0 or more of the previous character?: Match 0 or one of the previous character{2}: Match exactly two of the previous character{1,3}: Match 1 to 3 repeats of the previous character

re.findall(r"Kel*y", names)

re.findall(r"Kel?y", names)

re.findall(r"Kel{2}y", names)

re.findall(r"Kel{2,3}y", names)['Kelly', 'Kellly']9.3.3 Escaping special characters

With characters like * or ? or \ being given special roles in a regular expression, you might wonder how to actually find these exact symbols in a string?

The answer is that we escape the character, by putting a \ in front of it:

string_5 = "Are you *really* happy?"

re.findall(r"\*\w+\*", string_5) ['*really*']9.3.4 Look-ahead and look-behind

Lastly, sometimes we want to match a piece of a string based on what comes before it. For example, let’s return one last time to Moses and his toeses. To find all the verbs that Moses does, we want to find words that come after the word Moses:

re.findall(r"(?<=Moses )\w+", moses_string)['supposes', 'supposes', 'he', 'supposes']The (?<= ) part of the regex means “don’t actually match these characters, but look for them before our actual pattern”. This is called a look-behind.

Or, we can use (?=) to do a look-ahead:

re.findall(r"\w+(?= Moses )", moses_string)['but', 'as']9.3.5 Conclusion

The special symbols and structures for a regular expression are built into a programming language. python uses what are called perl-like regular expressions, which are the most common in modern languages. However, you may encounter other programming languages that use slightly different symbols to do various matching tasks!